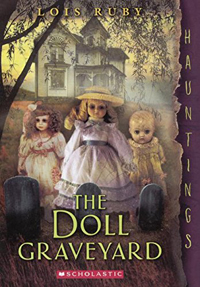

Ex-librarian Lois Ruby is the award-winning author of 18 middle-grade and young adult books. Whether the stories are contemporary or historical fiction, reality-based or paranormal, her characters are ordinary kids in extraordinary circumstances who always have options but don’t always make the best choices. Her latest novel, The Doll Graveyard, is a “gently spooky” work published by Scholastic Paperbacks (2014). You can find Lois on her website at LoisRuby.com.

What is your elevator pitch for The Doll Graveyard?

What is your elevator pitch for The Doll Graveyard?

What if you’re twelve-year-old Shelby, and you’ve just moved into a house populated by mysterious, mischievous, highly spooky dolls that refuse to stay buried in your backyard? And they keep changing before your eyes!

What unique challenges did this work pose for you?

I’m a person steeped in pragmatic realism. I don’t believe in supernatural hokum. But that doesn’t stop me from writing about it. The challenge for me is making it sound plausible, as if (under the right circumstances) everything in the story could happen. So, I had to avoid outrageous leaps that couldn’t, even by the wildest stretch, have realistic explanations. I also had to overcome my resistance to writing such an absurd story and cope with the truth: that I had a great time writing it.

What is it about your main protagonist that makes readers connect with her? Did your characters surprise you as you wrote their story?

My characters always surprise me. I do an extensive inventory on each of the main characters as if I were interviewing them for a biography. Just when I’m sure I know them, know what motivates them, know what stumps them or terrifies them, they turn on me and do something I never expected. What’s worse (or maybe it’s better) characters appear on the page that I never invited and sort of thumb their noses at me and say, “Hah! I’m here now, so what are you going to do about it?” My first inclination is to scold them and send them back into the hazy oblivion from which they reared their heads. Then I decide to trust them for a while and see where they lead me. Sometimes they’re pretty clever and bend themselves to just the plot turn I needed. As for my main protagonist in The Doll Graveyard, I hope what makes readers connect with her is that she’s normal, healthy, inquisitive, and secure in a loving family—but lonely and vulnerable just the same. Like the best of us in this life.

Tell us about the setting and why you chose it.

As I’ll explain later, the idea wasn’t my own. It came from a wonderful editor as just a wisp of a preposterous plot, with lots of freedom to develop it any way I wanted to. The only absolute was that there would be a girl named Shelby and a bunch of tiny dolls that refused to stay buried. I decided to set the story in a remote part of Colorado. Why Colorado? Honestly, because my only nonfiction book, which has garnered as much attention as, say, soggy coffee grounds, is entitled Mother Jones and the Colorado Coal Field War. I thought a paranormal novel also set in Colorado might cause a librarian or teacher or two to suddenly discover Mother Jones. (It didn’t work.) Anyway, Shelby’s house is one of two lone, scary old houses up on a hill in the middle of nowhere, and the graveyard behind the house is home to a bunch of small, mysterious graves. The novel has all the standard creaky floors and doors, hidden places and dark corridors savored in this sort of story, plus creepy, misbehaving dolls.

Is there a scene in the book you’d love to see play out in a movie?

Oh, yes! There’s a scene at the end of the book where all the disparate characters come together in the graveyard for a funeral for the stubborn dolls, each of whom represents something dramatic that happened in the history of the house. Now each doll merits a touching testimonial, as he or she is laid to rest. Good, satisfying ending. They’re buried for good, right? Believe me, my readers are sure they shall rise again! Do I hear sequel?

What makes this novel unique in the children’s/teen market?

I suspect it’s not unique but is rather one in a slew of gently spooky paranormals that tickle the fancy of young readers. And when I say gently spooky, that means nothing horribly violent happens. To the disappointment of children I talk to in schools, these dolls are not Chucky and Annabelle, the killer dolls. They’re just mischievous and stubborn and creepy. So, maybe I’m trying to say that what’s unique is that this book is relatively safe for readers who don’t want, or can’t handle, really intense supernatural or hyper-violent material, but still like chills to race up and down their spines.

Tell us more about the book: where the story idea came from, how long it took to write, editing cycle, etc.

As I mentioned, the idea came from an editor, generated in-house at Scholastic. But she gave me free rein to develop it any way I wanted and to complicate the story way beyond her expectations. I’ve often been chastised for including too many characters and too many complex issues in an otherwise simple story. That’s what makes it worthwhile for me. So, this was pure fun to write, and it wrote itself very quickly in about six months. I ran a fairly detailed plot proposal by the editor and got her go-ahead. Then she didn’t see it again until I’d written and revised it about six times. When next her eyes fell on it, she had some good suggestions for the logical tying up of loose ends, and for one or two more dramatic scenes, all of which I gratefully heeded. And then it took very little more work. This experience was totally different from the process of my more serious books; the books that consume me for two, three, five years; the books that touch my heart and challenge me after I’ve researched them to death, but aren’t as jaunty and fun to play with.

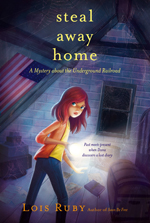

Steal Away Home (Aladdin Paperbacks/Simon & Schuster, 1994) is your most well-known book. Why do you think it continues to be so popular?

Steal Away Home (Aladdin Paperbacks/Simon & Schuster, 1994) is your most well-known book. Why do you think it continues to be so popular?

It’s an absolute conundrum as to why this book continues to have a vibrant life 22 years after publication, while so many of my other books have quickly vanished into the miasma. (As some famous author once said, “First you’re an unknown. Then you write one book and quickly sink into obscurity.”) I like to think it’s because Steal Away Home is a magnificent masterpiece of brilliantly universal appeal. Yeah, sure. There are a few more likely reasons. It’s set in Kansas in two periods—the present, and 1856. I wrote it while I was living in Kansas, and it caught immediate attention as a local book by a local author. But it moved beyond that designation and continued to be read in schools all over the country and in some foreign countries, as well. Right now it’s being used in a school in Kathmandu, Nepal, where I’ve been invited to speak. The main reason for its longevity, however, is that five years ago the state of Georgia adopted this novel for its fifth grade Civil War curriculum. So, this anti-slavery book has reached a much wider audience than I ever dreamed possible, and in a former slave state.

Knowing what you know now, what would you do differently if you started your publishing career today?

I would have found a young, hungry agent who would read my manuscripts immediately, make a few suggestions for quick revision, and submit them to a dozen editors at once. Alas, that’s not what I have, though—can I brag a little?—that’s what just occurred in my son’s life. He wrote a wonderful middle grade novel, found an aggressive agent who submitted it to eleven houses, and within a month he had three offers and just signed a contract with Random House. I, on the other hand, wait six months to two years for response. Often it’s a rejection, but after blubbering for a day or two, I ask my agent to send it out again. Sometimes she does.

What is your writing routine like? What is your writing process like? What part do beta readers or critique groups play in your writing process?

Calling it a routine is a big stretch, as each day is different, and life intervenes. What generally works is that I’m up about 5:30am, take care of a few emails that dared to come in while I slept, then get right to writing the ideas that I’d processed in those few precious minutes before I fell asleep the night before. About 8:30 I saunter into the kitchen for a cup of tea and a bowl of cereal. Then, on an ideal day, I return to the writing until noon. More likely, other pressing engagements, such as reconnecting with my sweet husband, or running errands, overtake my compulsion to write.

As for process, I do not outline a novel. I do extensive, character sketches of the principal people who populate (talk about alliteration!) the story at hand, and let them take over. I complete one scene, print, revise, print, revise, sigh, then move on to the next scene. When I think I’ve reached something approaching a cliffhanger after two or three conjoined scenes, I declare it a chapter and move on to the first scene of the next chapter. I keep revising the completed chapters maybe a dozen times more, until I discover that they’re woefully out of sequence. That calls for a detailed summary of what I’ve done so far, chapter by chapter, and then I begin shifting. Sometimes I jot a few key words of each scene on a Post-It note and tack them to the big picture window above my computer, then juggle Post-Its until something makes sense.

Now, about critique groups. I’ve been in some fabulous ones, in some humdingers, and a couple that did me little good because no one in the group understood how novels for youth were different from novels for adults. Still, any kind of critique group is better than laboring in the field alone without anyone’s help with the back-breaking (mind-bending) work.

If you suffer from writer’s block, how do you break through?

I don’t suffer from writer’s block. Just the opposite. I suffer from resistance to taking up the work in progress because I’ll be reluctant to quit and do something else that’s more necessary but less satisfying. I suffer from fear that I’ll submerge myself in my work, become a cranky hermit who never brushes her teeth and lives on cold pizza or macaroni and cheese, and neglects loved ones who deserve something better from me.

Do you have a message or a theme that recurs in your writing?

Message, no. But I discovered after about nine books, that a theme pervades all of them, despite their diverse subjects and eras. The theme is justice, whether I’m writing about abolition of slavery, faith healing, skinheads, the Battle of Gettysburg, Holocaust refugees in China, or even my sweetly weird paranormals. As it says in the Good Book, “Justice, justice shall you pursue.” I try.

How has the teen market changed since you first started publishing?

Interesting question that stumps me, yet one I’ve puzzled about quite a lot. In terms of the emotional preoccupations of young people, nothing has changed. There are still the terrors of the emotional dark, the confusion over identity and purpose, the family entanglements, and school. Books for this readership need to deal with those unchanging issues along with the joys and optimism of youth. But there are differences. Thanks to the Janus effect of technology, it being a blessing and a curse, kids have much more limited attention spans. You’ve got to hit them right away, scene by scene, and keep it short and immediate, or they abandon you. Harry Potter and a few other long and complicated books are delightful exceptions, of course. And books for teens are definitely edgier; there are no subjects, violent events, or unsavory language off-limits.

All the above is from the standpoint of subject and style. As for marketing, that’s where I’m clueless. I can’t fathom why some books get published and widely/wildly read, while others more worthy languish, if they see print at all. The one thing I do know is this: it’s no harder now to get published than it was 35 years ago when my first books came out. It’s always been difficult and very much a crapshoot.

Is there anything else you’d like readers to know?

Yes, I’ve got to add this: no matter how things change in history or in our social milieu, books for young readers must offer hope, must assure them there are caring and responsible adults to turn to, and must remind them that the universe is not indifferent to their highest aspirations.

KL Wagoner (writing as Cate Macabe) is the author of This New Mountain: a memoir of AJ Jackson, private investigator, repossessor, and grandmother. She has a new speculative fiction blog at klwagoner.com and writes about memoir at ThisNewMountain.com.

KL Wagoner (writing as Cate Macabe) is the author of This New Mountain: a memoir of AJ Jackson, private investigator, repossessor, and grandmother. She has a new speculative fiction blog at klwagoner.com and writes about memoir at ThisNewMountain.com.