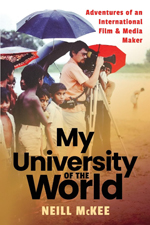

Neill McKee is a retired teacher, international filmmaker and multi-media producer, and an award-winning creative nonfiction author. He published his fourth memoir, My University of the World: Adventures of an International Film & Media Maker, in 2023. Look for Neill on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, as well as on NeillMckeeAuthor.com. To learn about his first three memoirs, read his 2019, 2021, and 2022 SWW interviews.

Neill, you’ve led a storied life. Please tell readers a little about your memoir My University of the World.

Neill, you’ve led a storied life. Please tell readers a little about your memoir My University of the World.

My University of the World (2023) is a stand-alone sequel to two of my other memoirs, Kid on the Go! Memoir of my Childhood and Youth (2021) and Finding Myself in Borneo: Sojourns in Sabah (2019). All three books can be enjoyed in any order you read them. This latest memoir is composed of 28 short chapters and an epilogue that takes readers on an entertaining journey through the developing world from 1970 to 2012. The book is filled with compelling dialog, humorous and poignant incidents, thoughts on world development, vivid descriptions of people and places I visited and worked in, and over 200 images.

The story starts when I became a “one-man film crew,” documenting the lives of Canadian CUSO volunteers working in Asia and Africa, and covers my marriage to Elizabeth, an American I met in Japan. Her life with me and her growth as an artist, as well as our children’s lives, are also covered in this new book.

Thirteen chapters document my time as a filmmaker for Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC), when I roamed the developing world and made about 30 films on many research projects in education, rural development, agriculture, post-harvest technology, fisheries and aquaculture, health care, water and sanitation—the list goes on. I wrote these stories to allow the reader to get a sense of the challenges I encountered. I kept the chapters light on technical details and full of humorous and poignant incidents. In each chapter, I also included how IDRC projects made an impact, or not.

The book also covers my time as a multimedia producer, leading teams of people in UNICEF in Bangladesh and Eastern and Southern Africa, and how my family adapted to a very different and interesting life. I ended up working for Johns Hopkins University, and then took over a project in Moscow, Russia. In my final job, I was asked to save a large project in Washington, D.C. from 2009 to 2012. By then I had learned a lot about managing people and, I must admit, sometimes I missed my years as a “lone-wolf” filmmaker at the beginning of my career.

Was it a natural transition for you to go from filmmaker to author?

Was it a natural transition for you to go from filmmaker to author?

During my career, I wrote three books and many articles on the role of communication in behavior and social change. But when I retired in 2013, I decided to turn to creative nonfiction writing. I submitted my first manuscript to about a dozen publishers and finally received two offers from small firms, but when I saw the contract details, I could see they were mainly interested in acquiring new titles with little or no resources for promotion. Also, despite the fact I had engaged a professional editor, they wanted to start over with that process. So, I decided to hire a professional book designer and self-publish. Either way, it was evident I was going to have to do the promotion myself. Perhaps if I was younger, I would have tried harder to seek an agent and publisher, but at my age, I didn’t think it made sense to wait. I don’t regret my decision because I have since learned that almost all authors, even if they do find a publisher, have to do or pay for most of the promotion themselves. With about 1,000 new books released every day in North America, in all genres, there is a lot of competition for readers’ attention. Fortunately for me, making money has not been a necessary objective in my new “retirement career.”

What was the most rewarding aspect of writing My University of the World?

I entered this memoir in several contests and so far have won two awards: Distinguished Favorite, Independent Press Award (2024) for Career; and Finalist, Book Excellence Awards (2024) for Autobiography. It’s rewarding to get such feedback, as well as good reviews on Amazon and Goodreads—some from people who have had no experience in international development work or film and media production. They simply enjoyed riding along with me, and some wrote that they felt they were there. Another benefit of writing this memoir was helping me sharpen my long-term memory, revising connections with old friends and former colleagues in Canada, the US, and around the world.

Do you have one place of travel that has left an indelible mark on you?

I would have to say it is Sabah, Malaysia, on Borneo Island, and the small town of Kota Belud near the coast of the South China Sea. That’s where I “found myself,” learning Malay language and teaching beautiful students, visiting their kampongs (villages), roaming around on my motorcycle, climbing Mount Kinabalu (the highest in Southeast Asia), having a few love affairs, and making my first film. It is all in my memoir Finding Myself in Borneo. That book has won three awards.

Was there anything surprising you discovered about yourself while writing your memoir?

Was there anything surprising you discovered about yourself while writing your memoir?

I found that I always had a knack for creative writing but never developed it until I retired. I never kept a diary but I had a lot of stories in my head for years. I wrote up some of these at the time they happened and kept a file. I found many more in old letters to and from my fiancé/wife and family, plus official trip reports that I always tried to make entertaining, including all the funny happenings along the way. Some of my colleagues might not have appreciated such embellishments, but I didn’t care. I had the feeling I would use these someday.

What was your favorite part of putting this project together?

Besides the creative writing, it was returning to IDRC in Ottawa, Canada, to look through a library of thousands of colored slides I had taken all over the developing world, many of which I used in the book. I also searched film archives and websites and managed to locate most of my film and media projects. This also helped to bring back my experiences over the years, and I decided to create a digital library, housing all I could find on https://www.neillmckeevideos.com.

The videos play on YouTube and I get great satisfaction from messages I receive every week from young adults who were influenced in their childhoods, especially from my most successful multi-media project, the Meena Communication Initiative for girls’ empowerment in South Asia.

Do you have a favorite quote from My University of the World you could share with us?

That’s a difficult thing for a writer to answer, but I think the opening paragraph of Chapter One gets the reader into the spirit of the memoir:

As I rolled across the plains of northern India in December 1970, on a rickety old train, rumbling between station stops and passing many smaller ones, I soon got into the stride of things by listening to Santana Abraxas through the earphones plugged into my compact reel-to-reel tape recorder. From that time on, the song Black Magic Woman became forever embedded in my mind as a part of India. The time was magic for me because I was on the road, filming and photographing Canadian volunteers in Asia. It was exactly what I wanted to do with my life—an answer to my prayers, or I should say to my meditation sessions. I was more in touch with Zen Buddhism than Christianity in those days, like other North American youth—many of whom were hippies, or what we then called “flower children,” who traveled to the East in search of answers to life’s mysteries and their future paths.

Does meditation play a role in your writing ritual today?

Does meditation play a role in your writing ritual today?

Well, I never got deeply into Zen Buddhism, but in my late twenties, I learned how to do Transcendental Meditation (TM) for practical, rather than spiritual reasons. My younger brother Philip had taken it up and even traveled to Spain to study at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s TM institute. In 1968, the Beatles had visited this Maharishi in India for spiritual replenishment, and by doing so, they helped spread TM worldwide. Philip taught me the basic method and gave me my secret mantra—a sound I repeated in my head for 20 minutes, two times a day, while breathing deeply, sometimes falling asleep, which was okay according to Philip. Eventually, I learned how to do this just about anywhere, even in noisy airports. Learning TM helped me survive the busy years of my career. I still use the technique for refreshing my brain cells while writing.

Is there anything else you’d like readers to know?

I chose to print and distribute through IngramSpark.com (IS), rather than going with Amazon alone. Through IS my books are available in North America and around the world on Amazon and many other platforms. Even independent bookstores and libraries can order copies. I publish in paperback and eBook formats, and two of my memoirs, Finding Myself in Borneo and Kid on the Go! were also produced as audiobooks by Lantern Audio, which distributes them very widely on many platforms as well. I promote through a growing email list, blog and review tours, and some social media channel posts, although I don’t put a lot of effort into the latter because it is evident to me that it doesn’t help much for sales, plus I am a bit allergic to simple messages, “likes,” and “congratulations,” etc., that have little substance or follow up. I find LinkedIn the most useful. I also put a lot of blog posts, interviews, links to reviews, places to buy, and awards on my author’s website: https://www.neillmckeeauthor.com/.

Su Lierz writes dark fiction, short story fiction, and personal essays. Her short story “Twelve Days in April,” written under the pen name Laney Payne, appeared in the 2018 SouthWest Writers Sage Anthology. Su was a finalist in the 2017 and 2018 Albuquerque Museum Authors Festival Writing Contest. She lives in Corrales, New Mexico, with her husband Dennis.

Su Lierz writes dark fiction, short story fiction, and personal essays. Her short story “Twelve Days in April,” written under the pen name Laney Payne, appeared in the 2018 SouthWest Writers Sage Anthology. Su was a finalist in the 2017 and 2018 Albuquerque Museum Authors Festival Writing Contest. She lives in Corrales, New Mexico, with her husband Dennis.