Are you a genre writer? Many people are – but most writers like to cross over into other areas besides the one in which they began. SouthWest Writers began as a group of romance authors back in the 1980s, but it quickly became apparent that writers from a plethora of other genres wanted to be able to locally network with bibliophiles, and at the time there were few other options outside of the university environment.

SWW still offers a wide variety of information and opportunities for anyone wanting to dive into the world of literature. Our membership ranges from neophyte scriveners to experienced professionals – it offers people who are well out of their school years a resource for understanding the ins and outs of writing.

When people want to focus on one specific genre they still want to be able to network with others of like mind. So SWW is happy to participated in cross-over events with groups who are focused on a specific style of writing. Right now, as we are holding the annual writing contest, we are delighted to be working with two local groups who will bring knowledge of their specialties into play when evaluating these entries.

The New Mexico State Poetry Society is scrutinizing our Free Verse, Limerick and Haiku categories. Shirley Blackwell, current Chancellor of the group, is coordinating the efforts of experts in each of those categories. NMSPS was founded in 1969. They are a non-profit poetry organization affiliated with the National Federation of State Poetry Societies, Inc. (NFSPS). Their mission is to promote the creation and appreciation of poetry throughout New Mexico. “We are a diverse and inclusive community of poetry aficionados whose collective purpose is literary and educational, with a good dose of fun thrown in.”

The New Mexico State Poetry Society is scrutinizing our Free Verse, Limerick and Haiku categories. Shirley Blackwell, current Chancellor of the group, is coordinating the efforts of experts in each of those categories. NMSPS was founded in 1969. They are a non-profit poetry organization affiliated with the National Federation of State Poetry Societies, Inc. (NFSPS). Their mission is to promote the creation and appreciation of poetry throughout New Mexico. “We are a diverse and inclusive community of poetry aficionados whose collective purpose is literary and educational, with a good dose of fun thrown in.”

For more information on NMSPS click here.

The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) is an international organization dedicated to helping authors  produce quality stories for young people. Their local chapter here in New Mexico is an excellent resource for new authors. Award winning author, Chris Eboch, has spoken for SWW on several occasions, and is coordinating the organizations participation with our writing contest.

produce quality stories for young people. Their local chapter here in New Mexico is an excellent resource for new authors. Award winning author, Chris Eboch, has spoken for SWW on several occasions, and is coordinating the organizations participation with our writing contest.

Writing for kids is not as easy as it might seem – especially since the abilities of children vary dramatically from year to year through high school! Have a good story is just the beginning – the same story would be written differently for a kindergarten student than for a middle grade child. Knowing how to focus your work is an art form integral to your success.

For more information on SCBWI New Mexico click here.

SouthWest Writers is very grateful for the assistance of these wonderful sister organizations and if your interests lie in these areas we encourage you to check them out!

Nonetheless, the writer can take some reasonable liberties with a memoir. Memoir, after all, derives from a French word meaning memory. So you’re drawing on your memories when you write a memoir. Yet many memoirs reproduce conversations of years gone by. Are they verbatim transcriptions that the writer is reproducing? Not likely. The reader should understand that the writer has reconstructed the events as he or she remembers them. In fact, a note early in the book might remind the reader that the writer is depending on memories to tell the story.

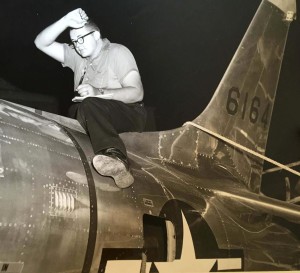

Nonetheless, the writer can take some reasonable liberties with a memoir. Memoir, after all, derives from a French word meaning memory. So you’re drawing on your memories when you write a memoir. Yet many memoirs reproduce conversations of years gone by. Are they verbatim transcriptions that the writer is reproducing? Not likely. The reader should understand that the writer has reconstructed the events as he or she remembers them. In fact, a note early in the book might remind the reader that the writer is depending on memories to tell the story. a speck in the ocean when you are flying thousands of feet above it and planning to land on the flight deck below. The carrier is not parked at sea when a pilot is trying to land. The ship is underway, rolling and pitching with the waves and the actions of the sea, plus it is steaming into the wind to grant the airplane extra lift as it makes its precarious landing.

a speck in the ocean when you are flying thousands of feet above it and planning to land on the flight deck below. The carrier is not parked at sea when a pilot is trying to land. The ship is underway, rolling and pitching with the waves and the actions of the sea, plus it is steaming into the wind to grant the airplane extra lift as it makes its precarious landing.

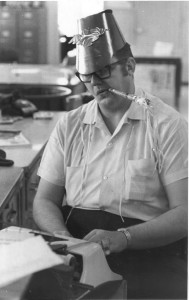

What can I say? This is my first attempt to do anything at all with a blog on a website. I’ve always wanted to, but haven’t had the time to learn. Suddenly I find I’ve accepted the challenge to learn how to make this work. My biggest fear is hitting the wrong button and screwing up entirely

What can I say? This is my first attempt to do anything at all with a blog on a website. I’ve always wanted to, but haven’t had the time to learn. Suddenly I find I’ve accepted the challenge to learn how to make this work. My biggest fear is hitting the wrong button and screwing up entirely